In Manitoba, Wab Kinew’s NDP government passed Bill 48 strengthening policies to incarcerate houseless peoples. The Protective Detention and Care of Intoxicated Persons Act came as no surprise for Indigenous peoples with boots to the ground for decades, who are advocating for harm reduction not violent “public safety” policies. The new law is not progress but centralist at best, conservative at worst, regression of Canadian politics, and reassertion of colonial carcerality carefully framed as “Indigenous governance.”

Wab Kinew’s Manitoba NDP government introduced the Your Way Home: Manitoba’s Plan to End Chronic Homelessness strategy in January 2025. Rather than focusing on policy-research backed solutions like social support, housing infrastructure, and harm reduction, Kinew took a policing approach to address the Indigenous housing crisis.

Bill 48 increases possible detention of publicly intoxicated peoples from 24 hours to 72 hours. Even if those arrested under the changed law are taken to a “designated protective-care centre,” this still represents forcible detention harkening back to the days when Indigenous land and rights were taken through legal force.

The legislation is the extension of colonial era policies that punishes systemic poverty and governmental neglect in Canada, framing Indigenous existence as criminal presence in public space. This law reinforces the false binary that some lives need to be contained to protect others, when increased support to harm reduction is what Manitoba needs: housing, social and health care, and equitable distribution of public resources.

Representation and “Indigenous Governance”

Kinew’s policy shows the increasing centrism and conservatism of all political parties in Canada. The Manitoba NDP government framed Bill 48 as a “public safety measure.” At a press conference, Kinew stated: “We need to take [houseless peoples] off of the street, in the name of public safety.” Kinew’s words dripped with the neoliberal discourse of federal Liberals and provincial Conservatives.

In Canada, “public safety” suggests a right given through engagement with civil Canadian society. In other words, the systemic privilege of home ownership, during a national housing crisis, and private space to be intoxicated. Historically in Canada, Indigenous, Black, and migrant folks have been systemically denied access to home ownership, and countless civil and civic rights. Kinew’s new policy works in service of predominantly white, affluent populations in Manitoba, who secured their status through generations of systemic neglect and violence towards Indigenous peoples.

Kinew has failed to represent Indigenous peoples, their voices, or their political will by framing incarceration as therapeutic and protective. Even after decades of activism and policy work from Indigenous peoples addressing the overcriminalization of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

At the Black and Indigenous Harm Reduction Coalition, we showed that the most effective “public safety” strategy is to house people, feed people, and provide care without conditions. Manitoba and Canada had decades to learn from its failures policing houselessness, from Winnipeg’s “sobering centers,” to the deep neglect of Indigenous communities left without housing and supports. Even with an Indigenous Premier, Manitoba and Canada polices the housing and opioid death crisis in Indigenous communities created by its own inequitable policies.

Kinew’s government, among others, have begun shifting towards progressive carcerality, and the expansion of policing and punishment often hidden behind political figures who are deemed “diverse.” From Toronto’s encampment evictions to Vancouver’s “Safer Public Spaces” initiatives, liberal and conservative governments across the country have opted for containment over harm reduction, similar to Manitoba’s NDP government. Canadian politics still treats Indigenous poverty as pathological rather than policy failure.

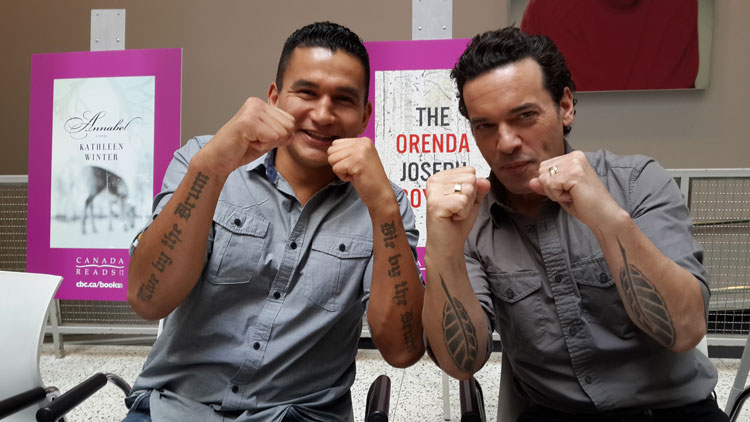

Grand Chief of the Southern Chiefs’ Organization Jerry Daniels (left) with Provincial NDP leader Wab Kinew at Victoria Inn during the Southern Chiefs’ Organization’s Economic Reconciliation Business Forum June 13, 2023 (Jessica Lee, Winnipeg Free Press).

Betrayed By Our Own

It is impossible to separate this new law from the history of the Premier himself. Wab Kinew, once criminalized himself, has been public about his own struggles with addiction and domestic violence. Once positioned as a hollow symbol of Indigenous resurgence, like many Indigenous leaders making their way through Canadian industries, Kinew now leads a government advancing policies that harm Indigenous lives.

Kinew’s turn toward carcerality is political and spiritual betrayal. Generations of Indigenous policy development and community work, grounded justice in kinship and harm reduction, have been silenced by Kinew’s NDP government. Expanding state control erases the work that has sustained our communities through centuries of colonial criminalization. In Canada, the Red cliff has arrived.

Generational Disillusionment

Kinew’s decision deepens generational disillusionment among Gen Z and Millenials towards Canada’s governance structures. Across Canada, young people are withdrawing from electoral politics that lack meaningful difference between liberal and conservative agendas.

Carney’s proposal to reduce international student numbers and increase costs for international students is quiet imposition of a new “head tax” on migration. Federal support for police expansion under the guise of community safety replaces increased support for Indigenous infrastructure in the 2025 Canada budget. Canadian democracy has collapsed into managerial centrism.

For a generation raised on promises of reconciliation, diversity, and inclusion, this is the hangover from the EDI era we warned about. This is representation that harms. Consultation without sovereignt(ies) for all Indigenous peoples. Inclusion masking material neglect. “Indigenous governance” adopted the carceral logics of the colonial state, and the moralist foundation of “progressive politics” became indistinguishable from the conservative order it once opposed.

Wab Kinew and authour Joseph-Boyden at Canada Reads 2014.

EDI Sovereignty

The rise of figures like Kinew, or even Jagmeet Singh, once signaled a hopeful, post-Obama liberal optimism, and a movement toward leadership reflecting Canada’s reality. Yet the EDI framework that made their rise possible has also hindered the political reach of Indigenous leadership and the communities Indigenous leaders supposedly represent. EDI promised to change who holds power, but did not change how power operates. EDI did not shift work cultures in universities, government, or other public sectors. In fact, it created a new form of human rights grievance against Indigenous populations by ushering in the pretendian generation in spaces of culture and heritage management. EDI celebrates individual ascent, careerism and inclusion, rather than collective transformation.

Kinew’s policy is a predictable outcome of representation politics detached from sovereignt(ies), abolition, and the will of Indigenous peoples. While Kinew is Indigenous, and there is no argument about his acceptance in his own community, the structures into which he has been invited remain colonial, carceral, and capitalist, despite his inclusion. The state can accommodate good Indigenous peoples, but not Indigenous dignity.

Indigenous sovereignt(ies) requires dismantling the colonial categories of “public safety” and “disorder” that justify violence against the unhoused and intoxicated. It demands that we understand harm reduction not as a health intervention but as a governance model. It demands a future that centers kinship, harm reduction, and accountability.

Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew, left, and Manitoba Métis Federation President David Chartrand unveiling a new plaque for Louis Riel’s portrait at the legislature on Monday (Gilbert Rowan, Radio-Canada).

Abolitionist Futures

When discussing abolition and decolonization in policy-related environments, those of us serving our communities are consistently told by academics, managers, and executives that our goals are unrealistic. This is evocative of the lack of breadth education many of these figures received before they were jettisoned to leadership positions during the EDI era.

Abolition is not about the absence of structure. Abolition doesn’t remove harm to create more harm. Abolition is acknowledging the context of our apocalyptic present through presence of kinship and harm reduction. When people have safe housing, meaningful community, and accessible support, the need for police and prisons dissolves. This is not utopian or liberal. It is materialist feminism, grounded in lived reality, not opaque, sensationalist, and centralist politics. The data from harm reduction workers, Indigenous-led healing communities, and housing initiatives are clear: harm reduction works, criminalization kills.

As an Indigenous leader, Kinew has a sacred responsibility to his people not to replicate colonial systems but to transform them. His government’s law threatens to undo decades of hard-fought Indigenous policy work that envisioned justice beyond punishment. It collapses the distinction between reconciliation and recarceration, and signals to young people that politics will always choose control over kinship.

The irony is that Kinew’s own survival is evidence of what non-carceral intervention can achieve. He was not saved by a jail cell after his charges. He was saved by community, kinship, and the possibility of redemption. Yet his legislation would deny that same possibility to our communities, who now face yet another state apparatus ready to decide who deserves freedom.

Harm Reduction

River Watch is a harm-reduction and community-safety initiative operated by CommUNITY204, a grassroots organization based in Winnipeg’s North End. The program deploys volunteers and outreach workers in boats along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers to engage directly with encampments and individuals living near the riverbanks. Many of these encampments formed small ad hoc Indigenous communities, much like the hunting grounds that became my mixed Nation, Valley River, during colonial era policy. The communities at these encampments have even started to erect tipis, and see the encampments as an extension of their own sovereighnt(ies).

Operating several days a week during warmer months, River Watch crews conduct wellness checks, deliver food, water, and harm-reduction supplies, and coordinate emergency responses. The team often serves as an early warning system for environmental or safety hazards, such as flooding, extreme weather, or medical crises affecting encampment residents. They do more to ensure the safety and survival of the populations they support than the NDP government.

River Watch embodies Indigenous-led and community-based harm-reduction principles, prioritizing kinship, support, consent, and relational accountability rather than surveillance or coercive interventions. By meeting people where they are at, a founding principal of the Black and Indigenous Harm Reduction Coalition, River Watch challenges dominant, carceral approaches to houselessness that rely on police displacement or forced sheltering.

Indigenous and abolitionist traditions have long shown that governance can be mutual aid, not control. Sovereignty can become collective imagination. Justice can be refusal. While Kinew is otherwise obliged as the smiling Red face of a carceral government, the rest of us will continue to build. Because, as front line workers, we know that this law will impact primarily Indigenous peoples, women, children, queer, and trans peoples. Native children will be removed from their parents at expanding rates, contradicting the proposals of Kinew’s Minister of Families, Nahhani Fontaine. Every child matters, until it’s time to actually enact policy that protects Indigenous children and families.

As film director Cera Yiu recently summarized, abolition is built on a principle that all people deserve dignity. Not only Natives with six figure salaries and degrees, Native men, and good victims. Not only white Indigenous peoples. All Native peoples deserve dignity and kinship, especially in their territories and homelands.

Leave a comment